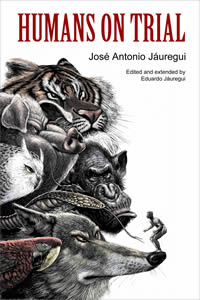

Humans on Trial

My father’s book Juicio a los humanos, which I edited and completed after his death in 2005, is now available in English both for Kindle and in other ebook formats.

Jane Goodall, the celebrated primatologist, environmentalist and UN Messenger of Peace (and one of the most inspirational people I have ever met) has been kind enough to write a new foreword for the book, which I enclose here in full:

Let me start by thanking Wamba the Ape, Taiji the Turtle and all of the other wonderful creatures (especially Fee the Mosquito, as you will see) who have invited me to present this extraordinary book to the English-speaking world. I first heard about it during a visit to Madrid in 2007, when I was introduced to Eduardo, son of the anthropologist José Antonio Jáuregui. Eduardo told me that his father had been unable to complete the manuscript before his death but that he, Eduardo, had undertaken to finish and publish it. As it was in Spanish, I could not read it, but I was fascinated by Eduardo’s account of the story and encouraged him to translate it into English. Humans on Trial is the result.

Let me start by thanking Wamba the Ape, Taiji the Turtle and all of the other wonderful creatures (especially Fee the Mosquito, as you will see) who have invited me to present this extraordinary book to the English-speaking world. I first heard about it during a visit to Madrid in 2007, when I was introduced to Eduardo, son of the anthropologist José Antonio Jáuregui. Eduardo told me that his father had been unable to complete the manuscript before his death but that he, Eduardo, had undertaken to finish and publish it. As it was in Spanish, I could not read it, but I was fascinated by Eduardo’s account of the story and encouraged him to translate it into English. Humans on Trial is the result.

It is a delightful story, presented as a fable, that will appeal to readers of all ages. There is courtroom drama, gripping suspense, memorable characters and witty repartee. It is a tale that entertains while, at the same time, it raises important ethical issues concerning animal welfare and environmental stewardship. It forces us to think about humanity’s true place in the natural world.

As we read we find ourselves, right from the start, immersed in a surreal judicial procedure – carried out under the Law of the Jungle. It is we humans who have been placed in the dock, accused by the animals of countless heinous crimes. And there we must remain as, one after the other, representatives of the different animal species stand to give evidence – damning evidence – of the heartless cruelties which humans beings have inflicted on the rest of the animal kingdom. And also, incidentally, on each other. As the evidence mounts against our species, we are forced to think deeply about these accusations. It engenders a growing sense of shame so that we are humbled by those animals who dare to stand up and speak in our defence.

I am no stranger to this sense of shame for I have long deplored the arrogance of those who believe that we humans stand apart from other animals, isolated by a false sense of superiority. In my years living and working with chimpanzees in the forest of Gombe, I was able to collect compelling evidence that there is, indeed, no sharp line dividing us from them. There are differences of course, but they are of degree, not of kind as many once supposed. Chimpanzees use and make tools. They learn by watching and imitating. They play and laugh. Like us, they have a dark side to their nature, and are capable of waging a kind of primitive warfare. But they also help each other and are capable of altruism. They show emotions such as happiness and sadness, anger and fear. They can suffer mental as well as physical pain. They have a sense of humour. They mourn the death of a family member – and may even die of grief.

And gradually, as scientists learned more and more about the natural behaviour of other animals with complex brains, it became increasingly clear that “animals” – by which we mean other than human animals – are not merely little machines operated by instincts – at least, no more than we are.

Reductionist interpretations simply did not explain complex social interactions or obviously intelligent behaviour. We humans were not after all the only beings with personalities, minds and feelings: in other words we were part of and not separated from the rest of the animal kingdom. (This was no surprise to me for I had learned it from the excellent teacher I had as a child – my dog, Rusty).

It was Darwin who first postulated, from a scientific view point, our kinship with other animals. But this has been understood for centuries – probably from the beginning – by the indigenous people of the world, by the Eastern religions, and by many others too. Saint Francis spoke of animals as his brothers and sisters. And Jose Antonio Jauregui, one of the foremost Spanish intellectuals, not only understood but also felt the kinship which we all share with other animals. His friend and sometime collaborator, the eminent American biologist Edward O. Wilson, writes that Jauregui had “an original mind of the first rank, [whose] best-known contributions have helped us understand the biological nature of the human mind”. But this book reveals also the compassion in Jauregui’s heart and the freedom of his spirit. It is this which breathes life into the animal characters of Humans on Trial.

Once we accept our kinship with other animals we are faced by any number of ethical concerns as we contemplate the ways we use and abuse so many of the amazing animal beings with whom we share – or should share – the planet. For, like many groups of human minorities, “animals” have long been cruelly enslaved, mistreated, persecuted – and sometimes exterminated. We imprison them in cages and exhibit them for our entertainment. We force them to pull or carry heavy burdens. We experiment on them for the supposed good of the human animal. We hunt them for sport. We raise them for food in factory farms. It is a fact that millions of people think of and treat animals as ‘things’ rather than beings, not understanding (or not wanting to understand) our underlying kinship.

Humans on Trial makes us think through some of these things. Can we, as human beings, continue to tolerate the mistreatment of so many millions of other animal beings? Continue to condone the destruction of their habitats and the exploitation of the non-renewable resources of our planet for our own immediate gratification? And if the answer is “No!” then it means that each one of us must make a conscious decision to change the behaviour of our species – starting with ourselves.

We humans do differ from other animals in that we have extraordinarily highly developed intellects. I believe this was because, at some point in our evolution, we developed our sophisticated language. And this has enabled us, among other things, to speak to each other about our problems, explain our feelings, plead for justice. Other animals cannot speak for themselves in this way – except in fables. Humans on Trial provides animals with their own voices and allows them to speak to us. It is not easy to listen to some of these voices, raised in anguish or anger, for it drives home the magnitude of the injustices we have perpetrated. But listen we must. We are, it seems, in the midst of the sixth great extinction of animal species on Planet Earth, this one caused by human actions. And not only are we exterminating animals, but we are also destroying the very ecosystems on which all of us depend for our continued existence.

Humans on Trial is just a fable, but it is absolutely clear that we are, in fact, facing a real-life trial with the verdict in the balance, a verdict that will depend on our ability to turn things around and change the status quo. The indigenous people, before making any major decision, asked how it would affect their people in future generations. We tend to make decisions today based on “How will this benefit me, now?” Or how will it affect the next share holders meeting, in three months? And decisions based on criteria of this sort, whether made by individuals, corporations or governments, are slowly destroying our planet.

And so, in our real-life trial, we humans stand accused – not only by the animals but by our own children and grandchildren – of jeopardizing the future of life on earth. If we cannot change our ways future generations, suffering most terribly from our thoughtlessness and greed, will judge us harshly indeed.

There are many who think that, already, it is too late. But I believe that there is still hope, still a chance for our species to redeem itself. But only if each one of us rolls up our sleeves and accepts the challenge. Somehow we must rediscover our connection with the natural world, learn to hear and understand the other beings with whom we share the planet, listen to the pleading voices of the children. And make the necessary changes in our behaviour. I shall never forget the speech, given by my friend Angaangay Lyberth, an Inuit-Kallaalit elder, to a packed auditorium during the United Nations Millenium Peace Summit. “I bring you a message from the North” he said. “In the north the ice is melting”. He paused. “What will it take to melt the ice in the human heart?”

I hope that Humans on Trial will help to bring about this thaw – at least it will encourage many people to rethink their relationship with our animal brothers and sisters. In Spain and other Spanish-speaking countries, Humans on trial, to give this book its Spanish title, has already been highly successful. It has inspired several theatrical adaptations spreading its urgent but hopeful message to thousands of people. Most importantly it has led to numerous school projects, and it is by influencing the attitudes of our young people that hope for change most truly lies. Eduardo has told me his intention is to see his book turned into an animated feature film – this, I am sure, would have a tremendous positive impact worldwide.

Meanwhile, I shall ensure that the book’s message is shared with all the hundreds of thousands of members of the Jane Goodall Institute’s youth program, Roots & Shoots, that is active in 120 countries around the world. I know that it will resonate with youth, speak to their growing understanding of the urgent need for change. Help them to become better stewards than we have been of Mother Earth and all her children.

José Antonio Jáuregui and Eduardo, I salute you both. You have made a major contribution to the future of life, as we know it, on Planet Earth. And special thanks to Phee, the Mosquito!

Jane Goodall Ph.D., DBE

Founder – the Jane Goodall Institute

& UN Messenger of Peace

www.janegoodall.org